The State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) monetary policy committee (MPC) statement of April 4, 2023 contained a statement which may sound curious to a student of economics: “Broad money growth showed a slight uptick in February, primarily due to a significant expansion in net domestic assets of the banking system. This was largely on account of higher public sector borrowing as growth in private sector credit decelerated sharply to 11.1 percent in February 2023 from 18.6 percent in February 2022.” The money supply, in the textbook macroeconomic model, is set by the central bank exogenously. Why would an increase in the banking sector’s lending to the government influence the money supply and cause it to grow faster?

This makes more sense if we work with an endogenous money model which begins with the central bank setting an exogenous interest rate. The banking sector then meets the demand for loans after adding a mark-up to the base interest rate set by the central bank. The loans create bank deposits, and the creation of new deposits requires an expansion of the money supply and the monetary base. (While the idea of loans creating deposits might seem nonsensical from a textbook point of view, where deposits are first required to be present in order to make loans, it makes sense to people in central banking. See McLeay, Radia and Thomas (2014).) In other words, it requires the central bank to accommodate the lending needs of the banking sector which in turn are driven by credit demand. Thus the central bank is characterized as “accomodationist”, working with a horizontal money supply curve rather than the vertical one as in a standard textbook. (For an overview of endogenous theories of money and their comparison with the mainstream textbook model, see Palley (2013).)

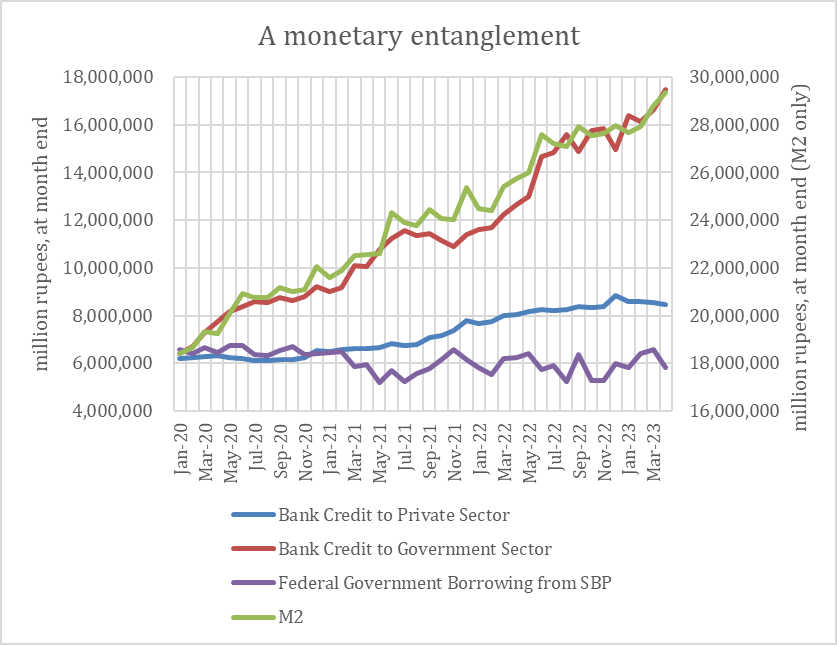

Now with this view in mind, the above quote from the MPC statement makes sense: the banking sector is focused on lending to the government rather than to the private sector, and that lending need is being accommodate by the SBP. What is really curious however, is that when we look at the numbers for the M2 monetary aggregate and the time series for scheduled banks’ credit to the government sector, the trend of these two series moves closely since January 2020. See the above chart. Extending the point from the MPC statement, it is plausible that bank lending to the government sector has been driving monetary expansion since before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic.

The very slow rise in the stock of bank credit to the private sector over this period could be taken as evidence for the argument doing the rounds that excessive government borrowing from the banking sector is crowding out credit to the private sector. This argument assumes that money is a scarce commodity. It is not. It is a credit and debt. (See Chapters 1 and 2 in Ingham’s The Nature of Money (2004) for a primer on the two competing views of money.) In theory, the government – any government – can create however much of it as it likes. There is, in theory, no restriction on the government issuing its own liability (which is what the rupee is to the Government of Pakistan). Which is exactly why lending to the government sector is attractive for the banking sector: governments are extremely unlikely to default on debt denominated in their own currencies as long as they can create the currency at will.

But here’s the rub: the government of Pakistan cannot create the rupee at will anymore following the 2022 amendment to the SBP Act of 1956. Section 9C in the SBP Act on the prohibition on government borrowing means that the Government of Pakistan has lost its direct money creation powers. Borrowing from the SBP, a bank owned by the government, was a money creation mechanism available to the government. The removal of that power adds a real default risk to the debt owed by the government sector to banks – a risk which doesn’t seem to be recognized by banks. The crowding out argument proponents seem to have a clear answer to the question of why banks aren’t lending to private business. But they are asking the wrong question. The real question is why banks think that lending to the government is low risk, and why they continue to lend to a government which has lost its independent money creation powers and must now rely on the private banking sector to create money endogenously, betting in turn on an accommodating central bank.

Even a recent story about Pakistani banks in Profit magazine, which is aware of the role the private banking sector is playing in helping the government create money, is off the mark about why lending to the government has become risky. The story claims it’s because of “all the talk of sovereign default” and the prospect of domestic debt structuring – but that talk has been about the government defaulting on its foreign debt denominated in foreign currency. The actual problem is the government’s domestic money creating capability. Given continued fiscal deficits, and in the absence of federal money creation powers, the only way the debt to the banking sector can be paid is through further government borrowing from the banking sector which is in turn accommodated by the central bank. The banks are betting that the SBP will continue to accommodate the government’s demand for private sector credit. How this bet will hold up under the pressure of deteriorating macroeconomic circumstances is anyone’s guess.

In any case, the result is that the banking sector, the government sector and the central bank now have an institutional relationship, a monetary-institutional entanglement if you will, which is full of heightened sovereign risk. If the government stops borrowing from banks, it will default on its debts to domestic banks. If the banking sector is no longer able or willing to lend to the government, it will collapse. If the SBP stops accommodating the banking sector’s lending to the government, the result is more or less the same. Should even one of the parties stray from the established pattern of behavior, the entanglement could lead to a great unravelling. But the trigger for a crash might come from other quarters. A bank run in the style of the Silicon Valley Bank, by depositors spooked by re-valuation of bank assets due to rising interest rates (and high default risk on government bonds in the Pakistani case), could also be possible.

The monetary entanglement described in this blogpost suggests some wider problems and questions which deserve consideration. As Dan Rohde has written recently in the Canadian case, “[p]rivately-owned, for-profit banks are still tasked with issuing the vast majority of our money, and this remains, in many regards, a very public mandate.” This is relevant in Pakistan’s case, and should encourage some reflection on the character and purpose of Pakistan’s central bank, the public significance of the private banking sector, and their respective implications for bank regulation. It is unclear how the present institutional entanglement might evolve for the better and evolve safely. Even if a great unravelling is avoided by some stroke of luck, questions will remain about the institutional architecture (including and especially checks on the sovereign) which would be appropriate and relevant for Pakistan’s unique macroeconomic challenges. Students of Pakistan’s macroeconomy have much work to do.

Notes on data:

The data is from two different data archive files from the SBP website’s economic data page.

- The series for (1) scheduled banks credit to government sector and (2) credit to private sector are from the data file for Credit/Loans Classified by borrower (under Banking Statistics). This data has monthly frequency and was last updated on May 29, 2023.

- The two series for (1) M2 and (2) federal government borrowing from SBP are from the data file for Broad Money (M2) (under Monetary Statistics). This data has multiple values every month, so the frequency is higher than monthly. Hence I have picked the latest number for each month, and in that way converted them into monthly series. This data was last updated on June 6, 2023.

- All four series graphed are from January 2020 to April 2023.

- The M2 series is graphed on the secondary (righthand-side) vertical axis.

Acknowledgments: Many thanks to Dr. Ali Cheema for his encouragement and comments on a previous draft. I am responsible for any mistakes and oversight.