To allow the market mechanism to be sole director of the fate of human beings and their natural environment indeed, even of the amount and use of purchasing power, would result in the demolition of society. For the alleged commodity ‘‘labor power’’ cannot be shoved about, used indiscriminately, or even left unused, without affecting also the human individual who happens to be the bearer of this peculiar commodity. In disposing of a man’s labor power the system would, incidentally, dispose of the physical, psychological, and moral entity ‘‘man’’ attached to that tag. Robbed of the protective covering of cultural institutions, human beings would perish from the effects of social exposure; they would die as the victims of acute social dislocation through vice, perversion, crime, and starvation. Nature would be reduced to its elements, neighborhoods and landscapes defiled, rivers polluted, military safety jeopardized, the power to produce food and raw materials destroyed. – Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation

For the past few weeks now I’ve been meaning to write an article about what I’m seeing happening in Pakistan. But the mental dissonance has been so great for me that I have not been able to sit and write coherently or for any extended period of time. I tried again yesterday but couldn’t write anything. All I managed was to piece together a few scattered thoughts on a Twitter thread. What you’re reading here now is the result of extending those thoughts a bit on the encouragement of a trusted friend and teacher. If I sound aggrieved, angry and disturbed, it is because I am.

It is not difficult to see that Pakistani society is in self-destruct mode. What we are seeing in Pakistan is a proper breakdown of the basis of social and communal life. This is the result of a conscious disregard for humanity. We are being told to carry on normally as much as is possible. We are being told inflation is down and the economy is stabilizing. Yet we are being told nothing can be done and that one shouldn’t say anything for fear of being abducted by the state, or worse. We are expected to pretend everything is fine and to keep up this farce. The self-deception is terrifying. I feel like I’m going mad.

In what problems do we see evidence of the breakdown? Take your pick: the murder of Ahmadis and Shias, failure to address Baloch and Pashtun grievances and the active suppression of their rights movements, frequent instances of mob lynching on allegations of “blasphemy”, air that burns the eyes and chokes the lungs, and now the murder of protestors the day before yesterday in Islamabad. I could go on.

What is especially bothering me personally is where universities stand in all this, because I have been involved in universities in one capacity or another for the past decade – a decade in which I’ve seen things from the perspective of a departmental student union representative, lecturer, teaching fellow, acting head of department, member of the board of trustees, and now an assistant professor. Universities make tall claims about the pursuit of truth, the spirit of inquiry, and creating change, but they are silent in the presence of widespread state violence and persecution. It is as if universities are aware of their irrelevance, having become part of the status quo long ago, knowing it’s too late to speak up now, knowing that any attempt to speak will be shut down with force because of how long universities have let themselves become comfortable as handmaidens of power. The continuous paeans to higher education and all the self-congratulation mean that universities may be one of the most dishonest modern day institutions. And universities are actively telling us that we, faculty and students, should carry on as usual. I increasingly wonder if I have a future in universities and whether I can find myself a different way of making a living. To continue in this line of work is a source of shame for me, and I do not know how long I can put up with this dishonesty.

The dishonesty extends particularly to how the significance of the public sphere is undermined and the private sphere valorized. We are increasingly told that we are to deal with public problems in an entirely private way: hire a security guard, install solar panels, drink Nestle, and buy an air purifier. The government itself is expected to run itself as if it were a business. Not surprising then, that interior minister Mohsin Naqvi is tweeting that “We apologize for the inconvenience over the past three days—these measures were necessary to protect citizens from the protesters.” – as if he was a customer service worker and not a minister in the federal government under whose watch protesting citizens have been killed by state forces in the national capital.

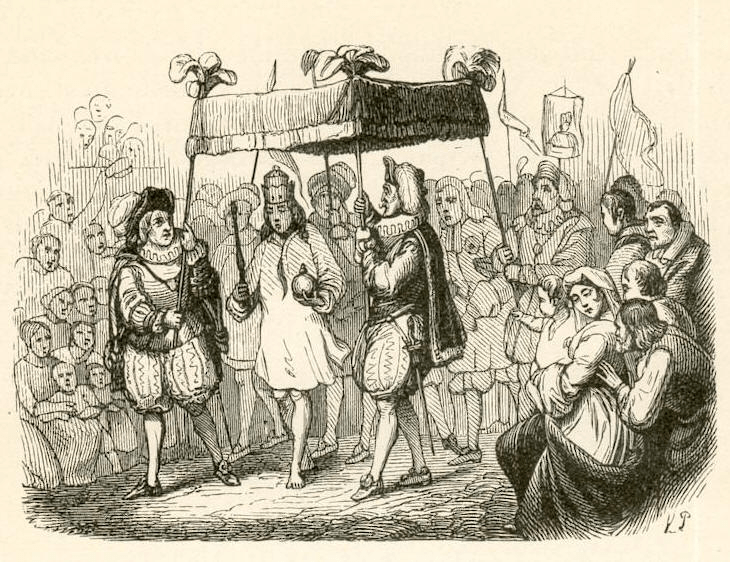

If the public are indeed customers, we are certainly not very happy. Public problems don’t really have private solutions, not good ones anyway, and so what we are feeling deeply is the absence of public and communal institutions which might help us address public problems. Yet our advisory elite continues to explain to us the supposed benefits of privatization and tells us to place our faith in what can really only be called a pathological belief that the pursuit of private interest will lead to the common good. These are, like Minsky’s economist-courtiers, our own darbari economists, seeking to influence would-be princes, curry favor with them, and do everything they can to not ruffle any feathers. The naked princes could turn mad and turn on their own advisors, after all. It is a sickening scene and I want to have nothing to do with these people.

Nor do I want to have anything to do with a government that is drenched in the blood of its own citizens. And the provincial government in Punjab, in as much as it is an extension of the federal government, is complicit. But alas, I am an economist, and economics is inextricable from policy and policy from government. Every economist seeks to influence, one way or another, ideas about economic governance. And if as an economist you want to have nothing to do with the government, you’re as good as a dead duck in the water. So I don’t know what I’m going to do from here on out. But I know something about what I’m not going to do, which is a blessing in itself.

Meanwhile, the gods of the marketplace slowly continue their work, as this calendar year is almost certainly going to be the hottest on record. That is, of course, not being taken seriously the world over. But November in Lahore this year has been noticeably warmer than any other November in my memory. It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that we’re in trouble. Universities have made themselves toothless and the economists are siding with the princes. If Pakistan’s social order is to have any chance to not collapse altogether under its own weight, forces of tyranny, isolation and dishonesty have to be opposed with a real collective determination and resolve far greater than is the case at the moment. That things could be worse is a chilling thought.

Let your anger turn to rust, gnawing at the bones of a thousand war machines. – Earth Liberation Studio

[The third thing] to give up is that you have nothing to do with princes and rulers, nor see them, because the spectacle of them, gatherings with them and socialising with them are a serious danger. …

[The fourth thing] to give up is to accept nothing of the benefaction of princes nor their presents, even if you know they were acquired legitimately. For expecting it from them degrades religion, in that sycophancy, partiality for them and complicity in their tyranny are produced by it. –al-Ghazali, Letter to a Disciple